Periods have long been a taboo subject, but there has been a shift in recent years, and we are now more openly discussing women’s menstrual cycle experiences. While there are many facets to this topic, here we’ll focus on training during your menstrual cycle. Menstrual cycles should be reasonably regular regardless of how much exercise training a female is doing. It should be noted that this may not be the circumstance for everyone, in which case I would strongly advise you to consult with your health practitioner if you haven’t already.

First up, let’s touch on what an eumenorrheic (normal or regular) menstrual cycle looks like.

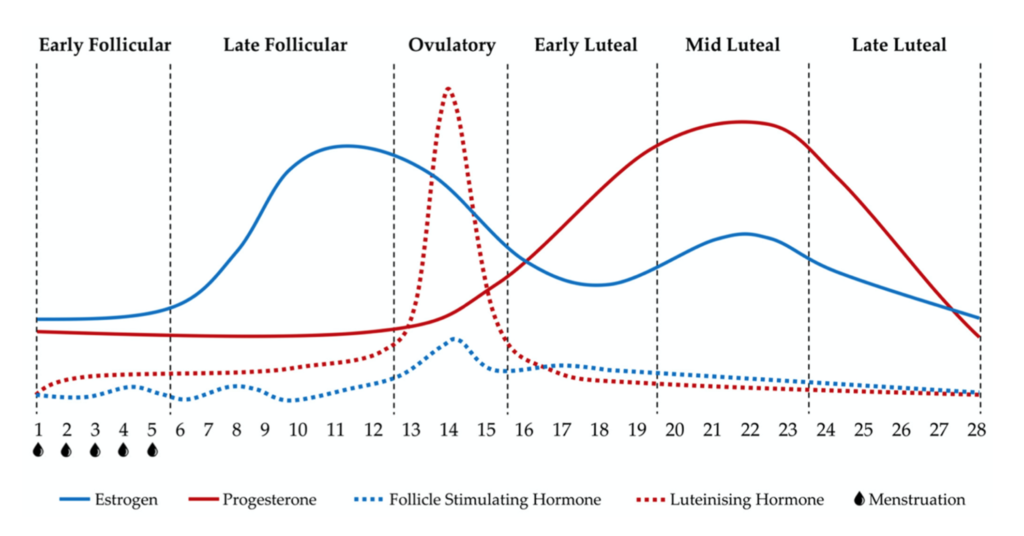

The menstrual cycle (MC) is commonly divided into three phases:

(1) the early follicular phase (FP): characterised by low oestrogen and progesterone, the pituitary gland releases follicle stimulating hormone (FSH).

(2) the ovulatory phase: characterised by high oestrogen and low progesterone, luteinizing hormone (LH) is released in response to the follicular phase’s rising estrogen levels, you may also see a rise in body temperature

(3) the mid-luteal phase (LP): characterised by high oestrogen and progesterone, PMS symptoms may be present here such as: bloating, headache, weight changes, food cravings, and trouble sleeping.

(Janse DE Jonge et al., 2019).

Below we will look at recent studies that have investigated the effects of the MC on a variety of strength and conditioning measures with the hopes to provide you with guidance when it comes to your own training or when training others. It should be noted that the menstrual cycle is only one hormonal profile; many women use an oral contraceptive (OC), which results in a different hormonal profile. The studies that follow will look at both women who use oral contraception and those who do not.

Julian et al. (2017) conducted research on the effects of menstrual cycle phase on physical performance in female soccer players. These players did not use any form of contraception. They concentrated on the early follicular phase (FP) and the mid luteal phase (LP), when hormones differed the most. They had the athletes perform the Yo-Yo, an intermittent endurance test, as well as a countermovement jump (CMJ) and 3x30m sprints. They discovered that Yo-Yo performance was significantly lower during the mid LP compared to the early FP. However, the CMJ and sprint performance results were both ambiguous. The findings of this study support the notion that there is a decrease in maximal endurance performance during the mid-LP which could be something to consider when performing endurance tasks eg a long run or longer machine efforts at the gym.

Sheila et al. (2011), on the other hand, investigated what effects the MC has on muscular strength (amount of weight you can lift). The study included nine healthy and physically active women. All had regular MCs, used oral contraceptives, and had at least eight months of resistance exercise experience. They performed a 10 repetition maximum (10RM) leg press, bench press, leg extension, and bicep curl. During the LP, there was a 5% increase in muscle strength during the leg press (the amount of weight pushed during a leg press). Aside from that, there were no significant differences between the phases suggesting it doesn’t play a role when it comes to muscular strength.

Rodrigues et al. (2019) expanded on this by comparing the maximal voluntary contraction (maximal force capacity of a muscle) of lower limbs in a leg press. The study included twelve healthy females who had been doing resistance training for more than three years but were not using oral contraception. The late LP showed the least muscle force capacity and the mid-FP had the greatest values of maximal muscle strength. This study suggests that different phases of the MC can produce different levels of muscle strength.

Wikström-Frisén et al. (2017) continued to look at lower limb resistance training. For four months, two groups did high frequency leg resistance training for two weeks of each menstrual cycle (including oral contraceptive cycle), followed by training once a week for the remainder of the cycle. Group 1 trained 5x per week for thefirst two weeks of each cycle, while Group 2 trained 5x per week for the last two weeks of each cycle. A control group did leg resistance training 3x per week consistently. There were no differences in training effects between those who used an oral contraceptive and those who did not. Overall they found group 1 got stronger than group 2 which tells us that training during the first two weeks of the menstrual cycle (FP) is more beneficial to optimise training than training during the last two weeks (LP).

McNulty et al. (2020) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 78 studies on the Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Exercise Performance in Eumenorrheic Women. According to the findings, exercise performance may be marginally reduced during the early FP when compared to all other phases. When researching the effects of the MC on performance, the most common comparison was between the early-FP and mid-LP. If we remember back to figure 1, we see the ovulatory phase where there is high oestrogen and low progesterone. None of the above studies touched on this phase and therefore perhaps future research should focus towards this.

Mcnamara et al., (2022) concluded that it is plausible that a ‘trivial’ effect of MC on performance may make a critical, albeit minor, difference in performance that athletes notice. Athletes chosen or expected to be chosen for the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games were asked to fill out a questionnaire about MC and performance. They discovered that two-thirds of elite female athletes perceive their MC influences their performance. Many reported they ‘felt’ as if their MC negatively affected their training. So even though we know the physiological differences are minor, if at all, it is important to note the psychological impact the MC can have on performance. If athlete’s feel as though their MC negatively effects their training, they are more likely to experience a drop in their mood during this time. This negative mood can lead to low preparedness to train/perform and this could indirectly link the MC to poor performance. Essentially they think their performance is reduced and by thinking this, their performance does become reduced by not for the reasons they believe.

So what does all this information tell us?

Some studies indicate an improved performance during FP and a decrease performance in LP whereas others have found no differences in exercise performance between MC phases. Essentially the information we have so far is contradictory and we are yet to reach a clear consensus.

Because of this, general guidelines on exercise performance across the MC cannot yet be formed. Therefore, we recommend a personalised approach depending on the individual’s response to exercise during their MC. Listening to your body and/or what your client is sharing with you will have a positive impact on both psychological and physiological mechanisms and help to encourage the development of healthy exercise habits.

for more on this topic and where this information came from:

Carmichael, M. A., Thomson, R. L., Moran, L. J., & Wycherley, T. P. (2021). The impact of menstrual cycle phase on athletes’ performance: A narrative review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(4), 1667.

Loureiro, S., Dias, I., Sales, D., Alessi, I., Simão, R., & Fermino, R. (2011). Effect of different phases of the menstrual cycle on the performance of muscular strength in 10RM. Revista Brasileira De Medicina Do Esporte, 17(1), 22-25. doi: 10.1590/s1517-86922011000100004

Janse DE Jonge, X., Thompson, B., & Han, A. (2019). Methodological Recommendations for Menstrual Cycle Research in Sports and Exercise. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 51(12), 2610–2617. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000002073

Julian R, Hecksteden A, Fullagar HHK, Meyer T (2017) The effects of menstrual cycle phase on physical performance in female soccer players. PLoS ONE 12(3): e0173951. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173951

McNamara, A., Harris, R., & Minahan, C. (2022). ‘That time of the month’ … for the biggest event of your career! Perception of menstrual cycle on performance of australian athletes training for the 2020 olympic and paralympic games. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 8(2), e001300. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2021-001300

McNulty, K. L., Elliott-Sale, K. J., Dolan, E., Swinton, P. A., Ansdell, P., Goodall, S., Thomas, K., Hicks, K. M. (2020). The effects of menstrual cycle phase on exercise performance in eumenorrheic women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 50(10), 1813-1827. doi:10.1007/s40279-020-01319-3

Rodrigues, P., Correia, M., & Wharton, L. (2019). Effect of menstrual cycle on muscle strength. Journal of Exercise Physiology Online, 22, 89-97.

Wikström-Frisén, L., Boraxbekk, C. J., & Henriksson-Larsén, K. (2017). Effects on power, strength and lean body mass of menstrual/oral contraceptive cycle based resistance training. The Journal of sports medicine and physical fitness, 57(1-2), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0022-4707.16.05848-5